Obstetrics and gynaecology can be a difficult specialty at medical school. A combination of medicine and surgery with many conditions that only exist during pregnancy, it can be a lot to get your head around!

In addition, O&G is often examined separately from the other specialities, sometimes earlier in medical school for finals with a limited amount of clinical time compared to the focus it may have in the curriculum. It is therefore crucial that the resources that you use to learn and revise obstetrics and gynaecology are concise, clear and above all memorable.

From the award winning Unofficial Guide to Medicine series comes The Unofficial Guide to Obstetrics and Gynaecology. This includes all core knowledge for medical school finals and beyond as succinct chapter summaries. You can then test your knowledge with questions, with fully expanded answers to give further theory and explain why you got the answer right (or occasionally wrong!)

Key Features

This multiple choice question book includes:

Dr Katherine Lattey BMBS MRes, Co-editor

Obstetrics and Gynaecology Specialty Trainee, West Midlands Deanery. Senior Clinical Research Fellow in Onco-gynaecological Robotic Surgery, University Hospitals, Leicester UK

With this textbook we hope to reduce the stress of revising for O&G exams. Too many obstetric text books can be written by senior doctors presenting their opinions, especially regarding those tricky “grey areas” of clinical practice.

We present the theory involved in a straightforward, clear manner. In a way I like to think that we’ve made your revision notes for you, so that you don’t have to!

Also if you like this book or others in the series get in touch, a few years ago I was reading one of the books and now I’ve edited one!

Dr Matthew Wood BM MRCOG, Co-editor

Foundation year doctor, St Mary’s Hospital, London UK

O&G is an exciting medical field. It can be hard to fully appreciate as often only a short time is allocated to the specialty at medical school, with a lot to learn in that time.

Each topic in this book is crafted for students, explaining the scientific principles behind each disease concisely, starting from the very basics, and then building upon this knowledge to explain the intricacies of investigation and management.

I believe that by teaching the fundamentals well, this book makes it easy for students to obtain an excellent understanding of O&G.

ORGANISATION AND PRINCIPLES OF ANTENATAL CARE

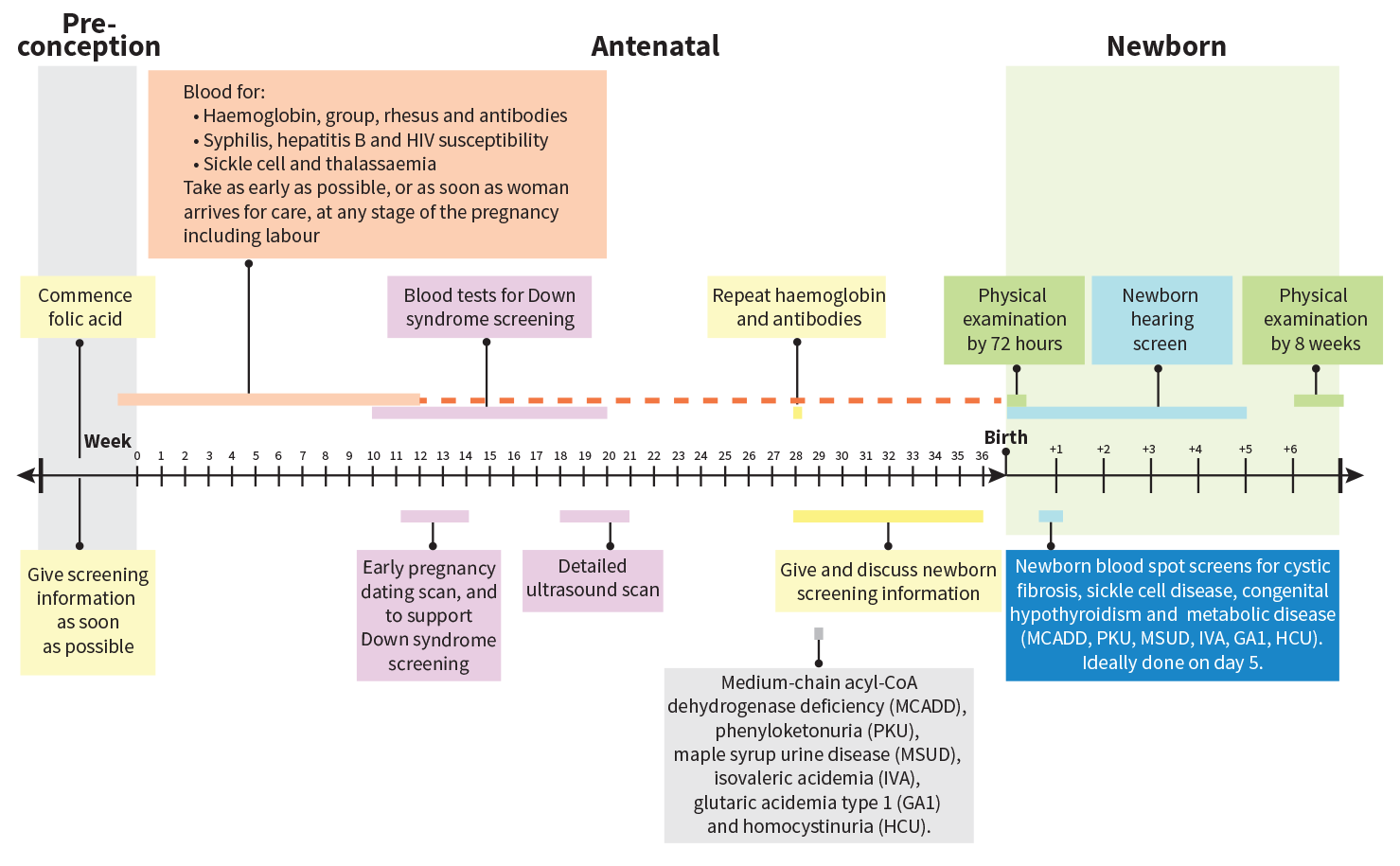

The World Health Organisation (WHO) advises that all pregnant women should be offered antenatal care (Figure 1). In the UK, this is primarily provided by midwives, with the support of primary care physicians, within the community setting.

Schedule of appointments

First contact with a healthcare professional

The first contact is almost always with the woman’s primary care physician. Primary care physicians are crucial in the antenatal and postnatal care throughout a woman’s pregnancy.

Upon initial contact, information regarding the following should be given to women:

- Folic acid and vitamin supplements.

- Smoking, recreational drug use and alcohol intake.

- Antenatal screening.

- Diet and exercise.

- Maternity benefits.

- Antenatal classes.

- The pregnancy care pathway.

Booking appointment

The second antenatal appointment is called the “booking appointment”, and ideally this should take place within 10 weeks. It is usually carried out by a midwife who will be assigned to the patient throughout the pregnancy. At this appointment, the woman should receive information regarding the pregnancy, particularly the screening tests available.

Early appointments facilitate rapid identification of the woman’s needs, and for any extra support to be put in place early. If risk factors that require obstetric input are identified, then the obstetrics team may see the patient throughout the pregnancy, in addition to her routine appointments.

The primary outcomes are to:

- Identify women who may need additional care or obstetric input according to:

- Past medical history, for example, epilepsy, hypertension.

- Past psychiatric history, for example, bipolar disorder, depression.

- Past obstetric history, for example, caesarean section, preeclampsia.

- Family history, for example, puerperal psychosis, diabetes.

- Social history, for example, smoking, drugs, female genital mutilation, domestic violence.

- Risk factors for venous thromboembolism – where significant risk is identified, low molecular weight heparin prophylaxis may be offered antenatally.

- Measure height and weight to calculate BMI.

- Measure blood pressure to identify pre-existing hypertension.

- Dip the urine for protein, nitrites and glucose to identify underlying renal disease, urinary tract infection or diabetes, respectively.

- Offer booking blood tests:

- Full blood count (FBC) – assess for anaemia, platelet count and haemoglobinopathies.

- Group and save (G&S) – blood group, rhesus D status, red cell alloantibodies.

- Microbiology – hepatitis B virus (HBV), HIV, syphilis.

- Offer urinalysis and mid-stream urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity (MC&S) to screen for asymptomatic bacteruria.

- Offer screening for Down syndrome – either blood tests, or combined ultrasound and blood tests.

- Offer early ultrasound scan (around 12 weeks’ gestation) to obtain an accurate estimation of gestational age, identify large structural abnormalities, determine the number of fetuses, and if the patient wishes, undertake the ultrasound part of the Down syndrome screening.

- The anomaly scan (offered at approximately 20 weeks’ gestation) enables further assessment of congenital abnormalities that may be more readily detected at this later gestation.

Single best answer, true or false and extended matching questions to enable you to really test your knowledge

Questions

Sandra, a 24-year-old woman, gravida one, is around eight weeks pregnant. She has suffered from nausea and occasional vomiting for the last four weeks. However, over the last week, she has been unable to eat, is only drinking small amounts and has been unable to work due to the frequency of her symptoms. She is exhausted and very upset. She has no past medical history and is taking no medication.

- Dopamine receptor agonist.

- Dopamine receptor antagonist.

- Histamine H1 receptor agonist.

- Histamine H1 receptor antagonist.

- Histamine H2 receptor agonist.

- Histamine H2 receptor

- Hydrogen/sodium ATPase inhibitor.

- Irreversible proton pump inhibitor.

- Nicotinic receptor agonist.

- Nicotinic receptor antagonist.

- Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor agonist.

- Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.

The following medications can be used in the management of hyperemesis gravidarum. To what class of drug do they belong?

Select the most appropriate option from the above list that corresponds to the following statements. Each answer can be used once, more than once or not at all.

- Q1 Cyclizine.

- Q2 Metoclopramide.

- Q3 Omeprazole.

- Q4 Ondansetron.

- Q5 Prochlorperazine.

- Q6 Promethazine.

- Q7 Ranitidine.

Q8 Which of the following is the major cause of hyperemesis gravidarum?

- Mass effect of the uterus pressing on the bowel and stomach.

- β hCG affecting the vomiting centres of the brain.

- Progesterone relaxing the lower oesophageal sphincter.

- Oestrogen delaying gastric emptying.

- Insulin-like growth factor (IGF1) causing insulin resistance and ketoacidosis.

Q9 Answer true or false to these statements regarding hyperemesis gravidarum.

- Ketonuria supports the diagnosis of hyperemesis.

- A raised haematocrit is a common investigation result in hyperemesis gravidarum.

- Ultrasound scanning should form part of first-line investigations in hyperemesis to diagnose molar pregnancies.

- Pregnancies troubled by hyperemesis are more likely to end in miscarriage.

- Hyperemesis commonly presents in the second trimester.

EARLY PREGNANCY COMPLICATIONS

Hyperemesis gravidarum

The following medications can be used in the management of hyperemesis gravidarum. To what class of drug do they belong?

Key Point

It is important to be familiar with common medications used in the management of hyperemesis. By understanding their mechanisms of action, it is much easier to recall their common side effects and interactions. When one medication is not adequately controlling a symptom, with good pharmaceutical knowledge it is easy to select multiple medications to treat the same symptom by different mechanisms.

- Mass effect of the uterus – Incorrect. Hyperemesis occurs in the first trimester. At 12 weeks, the uterus is usually only just palpable above the pubic symphysis and so is not large enough to cause compression of the intestine and stomach to cause vomiting. Later in pregnancy, the enlarging uterus can have an effect on respiration due to increased pressure abdominally, which pushes up on the diaphragm.

- ✔ β hCG – Correct. β hCG is produced by the placenta. It is at its highest concentration in maternal blood in the first trimester, between weeks 8–12 gestation, when most cases of hyperemesis present. It is thought to have a direct effect on the CTZ and vomiting centres of the midbrain, resulting in nausea and vomiting. Cyclizine, promethazine and prochlorperazine predominantly have their effects on these central nervous system areas.

- Progesterone relaxing the lower oesophageal sphincter – Incorrect. This is likely to have an effect on acid reflux and thereby contribute to hyperemesis, but is not the most prominent cause. Ranitidine and omeprazole can reduce acid production and therefore acid reflux symptoms.

- Oestrogen delaying gastric emptying – Incorrect. Like progesterone, this is likely to have an effect but is not the prominent cause. Metoclopramide is a dopamine antagonist which increases gastric emptying, so it may improve this aspect of hyperemesis.

- Insulin-like growth factor (IGF1) causing insulin resistance and ketoacidosis – Incorrect. There is no evidence IGF has any effect on hyperemesis. It is, however, very important in fetal growth.

Key Point

Hyperemesis gravidarum is likely to have multifactorial causation, including genetic, physical, biochemical, hormonal and psychological elements. However, hCG is thought to be the most important cause of symptoms.

Important Learning Points

- Hyperemesis gravidarum is a common early pregnancy complication, which is often self-limiting and resolves by around 16 weeks’ gestation.

- Treatment is simple, with most cases improving with a single antiemetic. Knowledge of the different antiemetics and their mechanism of action are essential when prescribing multiple medications to optimise patient condition.

- As well as antiemetic treatment, rehydration and antacids are the other treatment modalities.

- ✔ Ketonuria supports the diagnosis of hyperemesis – True. Recurrent nausea and vomiting causes a patient to lose her appetite and stop eating as ingestion of food and drink can increase the frequency of vomiting. Lack of nutrients, in particular glucose, causes the body’s metabolic pathways to change adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production from glycolysis to gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis. The resultant ketone bodies are excreted in the urine. A common misunderstanding, even among practicing clinicians, is that rehydration corrects ketonuria. However, this is not the case. Once the patient restarts eating, ketogenesis and gluconeogenesis stop and glycolysis restarts. Ketones are no longer produced, so they are no longer excreted in the urine.

- ✔ A raised haematocrit is a common investigation result in hyperemesis gravidarum – True. The haematocrit is the concentration of red blood cells in a blood sample. Dehydration results in decreased water in the intravascular space, so the concentration of cells increases, resulting in a raised haematocrit. In pregnancy, plasma expansion occurs naturally and decreases the concentration of red cells, causing a physiological anaemia and decreased haematocrit. It is important to remember that both dehydration and pregnancy are independent risk factors for venous thromboembolism, so patients with hyperemesis should have thromboprophylaxis as part of their management.

- ✔ Ultrasound scanning should form part of firstline investigations in hyperemesis to diagnose molar pregnancies – True. Hyperemesis is caused by raised β hCG levels. Β hCG is made by the placenta; therefore, a large placenta produces high concentrations of β hCG and can cause severe symptoms. The two conditions identified on early ultrasound scan that can cause elevated β hCG levels are molar pregnancy and twin pregnancy. Twin pregnancy results in a physiologically enlarged amount of placental tissue. The diagnosis of twin pregnancy is not essential before the routine 12 week gestation examination, but it can occasionally be helpful in identifying whether the pregnancy is monoamniotic or diamniotic. It is important, however, to diagnose and treat molar pregnancy as quickly as possible to improve the patient’s survival rate.

- Pregnancies troubled by hyperemesis are more likely to end in miscarriage – False. Actually, hyperemesis appears to be associated with fewer miscarriages than occur in the general population. It is thought that hyperemesis is a sign of high β hCG levels and good placental function.

- Hyperemesis commonly presents in the second trimester – False. Hyperemesis usually presents in the first trimester. The β hCG levels are highest around 8–12 weeks’ gestation and they drop in the second trimester, so most patients’ symptoms resolve by 16 weeks’ gestation.

Key Point

The investigation results of a patient with hyperemesis will show biochemical investigation results similar to any patient undergoing starvation. Knowledge of the likely abnormalities for these investigations will help when treating patients with starvation in other specialities. Understanding the process of ketone formation will also be of particular use in managing diabetic ketoacidosis.

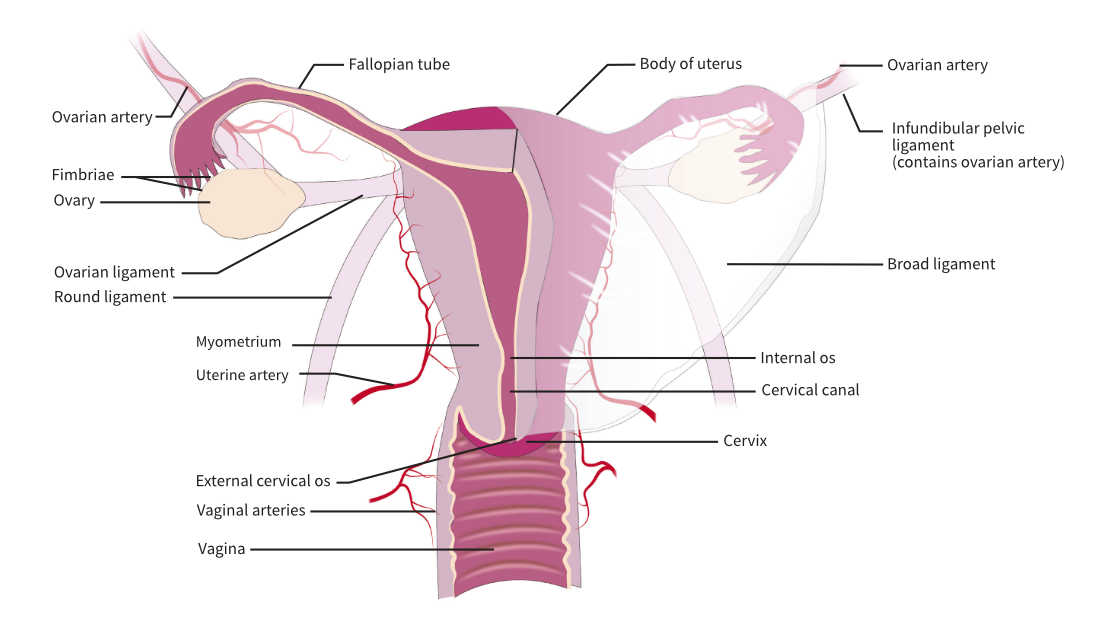

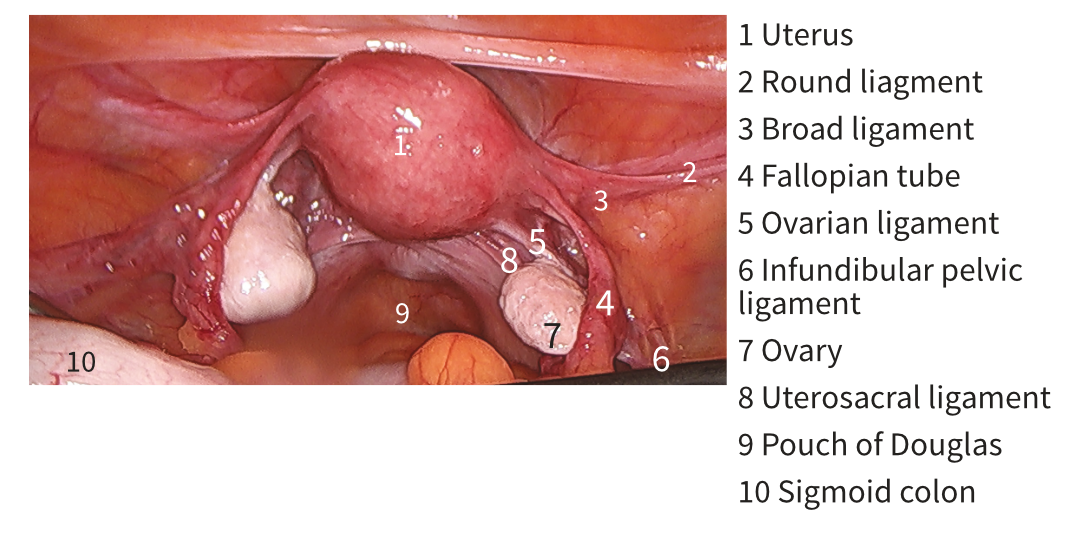

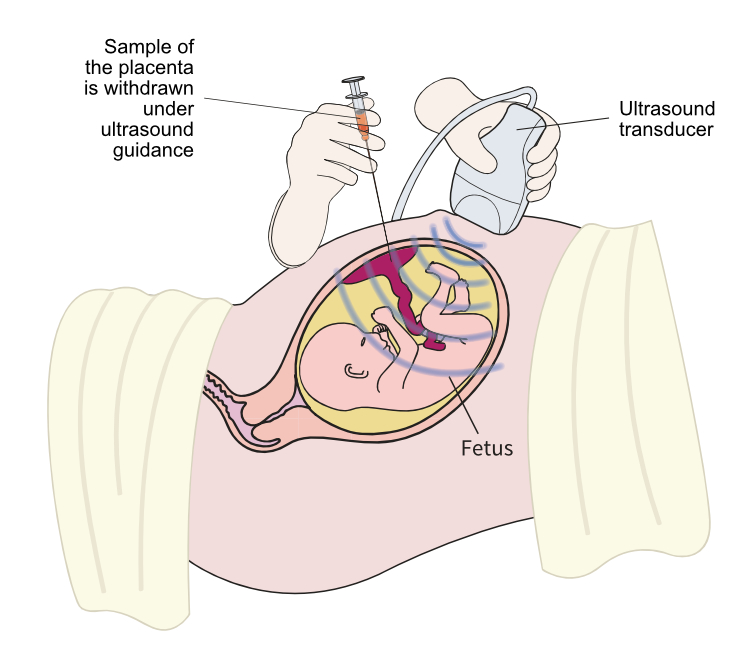

Colour images and illustrations to present key concepts and anatomy

Anterior aspect of the internal female organs

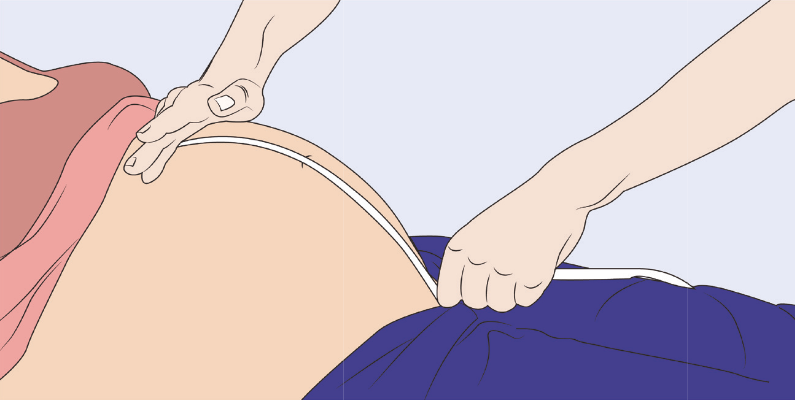

Cusco speculum

Contact Us

Are you a medical trainee, a student, a doctor or medical professional?

We’d love to hear from you for feedback or if you would like to contribute towards the Unoffical Guide to Medicine series.